My first tiny contribution to Librosa - a bug in waveshow

callbacks, garbage collection, and weak references

I recently helped close my first bug in librosa (yay!) where librosa.display.waveshow() could get "stuck" in envelope view instead of switching to sample view when zooming in (for example by calling ax.set_xlim(...)). The issue was initially described as "Matplotlib doesn't allow multiple attachments to the same event," which would explain why two wave plots on the same axes don't both update.

But while investigating, we discovered something different:

The exact same "stuck in envelope mode" symptom can happen even with one

waveshow()when the caller doesn't keep the return value.

That detail changed the diagnosis from "event system won't attach two callbacks" to "the object that owns the callback disappears."

We here explain how we got from that observation to a fix that both makes waveshow() reliably adaptive even if we ignore its return value, and

avoids a sneaky memory leak that a naive "just store it in a dict" fix would introduce.

The bug as users experience it

waveshow is "adaptive." It shows a waveform in a coarse summary form when zoomed out (so it's fast and readable), but when we zoom in enough it switches to drawing the actual samples (so we can inspect detail).

A representative repro looks like:

y, sr = librosa.load(librosa.ex('trumpet'))

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Plot 1

librosa.display.waveshow(y=y, sr=sr, ax=ax)

# Plot 2

librosa.display.waveshow(y=y, sr=sr, ax=ax, zorder=-1)

ax.set(xlim=[0, 0.025])

plt.show()As explained in the issue, the expected behavior was that, after zooming to a tiny time window, the plot should switch to sample view. What actually happened was that it stays in envelope view - no matter how much we zoom.

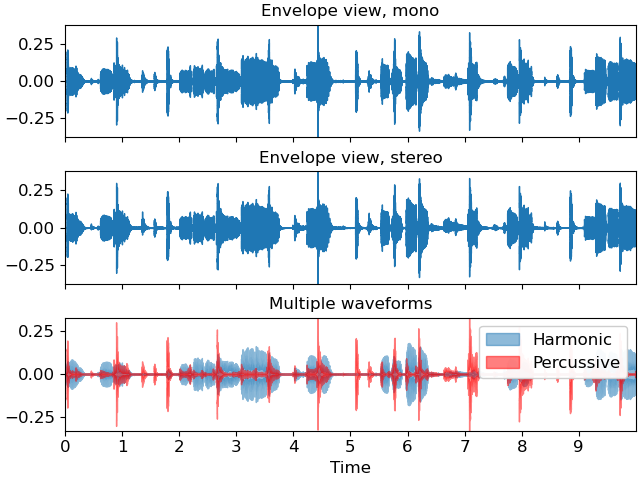

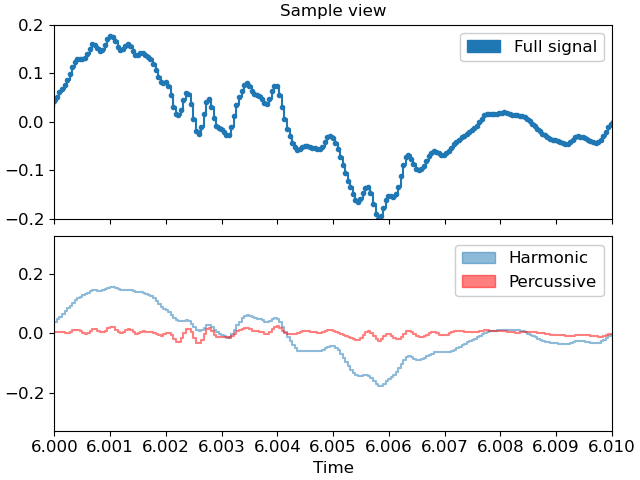

What "envelope view" vs "sample view" means

Before we talk about callbacks and garbage collection, it helps to be very clear about what the two modes look like. The entire bug is basically "the display never transitions from A to B."

Envelope view (zoomed out)

When viewing a longer time span, plotting every sample would be a dark solid blob. So waveshow summarizes: it draws something like a filled band that represents the overall amplitude envelope.

Sample view (zoomed in)

When we zoom in far enough (milliseconds), individual samples become meaningfully spaced apart. In this mode, waveshow draws the actual samples - often as a step-like line that makes the discrete nature obvious.

The failure mode is: we zoom in, but the plot stays in the envelope representation. That means the "switching logic" isn't running when the viewport changes.

The key clue: it can fail even with a single plot

The issue thread originally framed the problem as "multiple adaptive waveshows can't attach callbacks properly", but while debugging, I found the bug even with one plot, when I didn't assign the return value.

librosa.display.waveshow(y=y, sr=sr, ax=ax) # return value ignored

ax.set_xlim(0, 0.025)If we do store the return value somewhere, it keeps working as expected.

That is a huge clue, because it implies:

- The adaptivity depends on an object returned by

waveshow() - If we don't keep that object alive, adaptivity would break

At that point I suspected that garbage collection was deleting something essential. To understand why, we need a bit of background about how Matplotlib structures plots and how it stores callbacks.

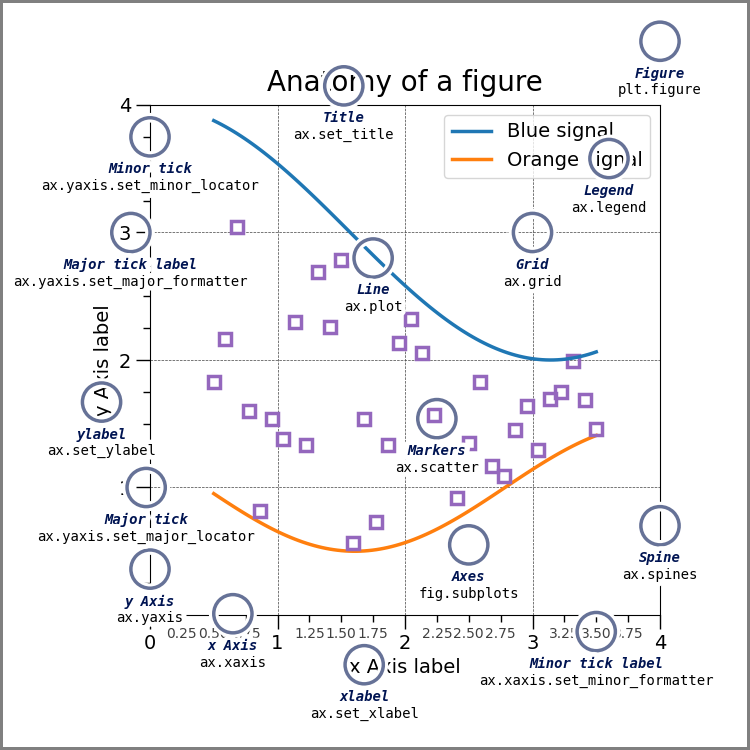

Matplotlib background (Axes, Artists, callbacks)

This section is not "Matplotlib 101." It's just the minimum vocabulary to explain why our objects can vanish and why memory leaks can happen. The diagram below labels the key components we'll reference:

Figure vs Axes

A Figure is the whole canvas/window.

An Axes is the actual plotting area inside the figure. It has the coordinate system and stores view state like x/y limits. When we write:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()ax is the Axes.

When we call ax.set_xlim(...), we're changing Axes state.

Artists: the things that get drawn

In Matplotlib, an Artist is anything drawable: lines, text, patches, filled regions, etc. For this bug, the important thing is that waveshow() typically creates two artists:

- one artist representing the sample view (often a

Line2Dfrom something step-like) - one artist representing the envelope view (often a filled region, like a

PolyCollection)

Then it toggles their visibility based on zoom level.

A quick note on strong vs weak references

In Python, a reference is how one object "knows about" another object. When we write x = some_object, the variable x holds a reference to that object. When one object stores another as an attribute (self.data = some_object), that's also a reference.

A strong reference is the default kind. It expresses ownership or dependency: "I need this object." Python tracks how many strong references point to each object (this is called reference counting). An object stays alive as long as at least one strong reference to it exists.

a = [1, 2, 3] # 'a' is a strong reference to the list

b = a # 'b' is another strong reference to the same list

del a # list still alive - 'b' still references it

del b # now the list has zero strong references, so it's freedA weak reference (via Python's weakref module) is different: it's a reference that explicitly does not express ownership. It says: "I'd like to access this object if it's still around, but don't keep it alive just for me." Weak references don't increment the reference count.

import weakref

obj = SomeClass()

weak = weakref.ref(obj) # weak reference - doesn't keep obj alive

print(weak()) # returns obj (it still exists)

del obj # no more strong references

print(weak()) # returns None - obj was collectedThe main difference is that strong references keep objects alive while weak references merely observe them. This matters a lot for understanding this bug.

In Matplotlib, artists typically hold a strong reference back to their owning Axes. This means that if we have an artist, we can usually get to its Axes via something like artist.axes, and that relationship is strong.

Callbacks: how "adaptivity" is triggered

How does waveshow notice that we zoomed? It registers a callback.

A callback is simply a function we hand to another piece of code, saying: "call this function when something interesting happens." The act of handing it over is called registering the callback. In Matplotlib, we can register callbacks for various events like mouse clicks, figure resizes, or (relevant here) axis limit changes.

def on_xlim_change(ax):

print("x-limits changed!")

ax.callbacks.connect('xlim_changed', on_xlim_change)Now whenever the x-axis limits change (e.g., via ax.set_xlim() or interactive zoom), Matplotlib calls on_xlim_change.

Bound vs unbound callables

In the example above, on_xlim_change is a plain function. It has no attachment to any particular object. But in waveshow, the callback is a bound method:

class AdaptiveWaveplot:

def update(self, ax):

# switch between envelope/sample view based on zoom

...

adaptor = AdaptiveWaveplot()

ax.callbacks.connect('xlim_changed', adaptor.update) # bound methodWhat's the difference?

- Plain function: just code. When called, it receives only the arguments passed to it.

- Bound method: a method attached to a specific instance. When we write

adaptor.update, Python bundles together the functionAdaptiveWaveplot.updateand the specific objectadaptor. When called, that object automatically becomesself.

# These are equivalent:

adaptor.update(ax) # bound method call

AdaptiveWaveplot.update(adaptor, ax) # unbound call with explicit selfThe crucial point is that a bound method holds a reference to its instance. So when Matplotlib stores adaptor.update as a callback, it's storing something that refers back to adaptor. This is where object lifetimes start to matter.

The real root cause: Matplotlib stores bound-method callbacks weakly

Matplotlib stores some callbacks (including bound methods) using weak references.

That design choice is reasonable. If Matplotlib stored every callback strongly, it could accidentally keep user objects alive forever. But it also means that if we don't store the return value, the callback will be garbage collected.

Remember: waveshow() creates an adaptor object (e.g. AdaptiveWaveplot) and registers the adaptor's update() method as the callback. So there is a chain:

- Axes changes xlim → Matplotlib tries to call → adaptor.update()

If the caller doesn't store the return value, there may be no other strong reference to the adaptor after waveshow() returns. Since Matplotlib's callback storage is weak, the callback registration does not keep the adaptor alive. Then, Python's garbage collector can and likely will collect the adaptor object. Once it's collected:

- the weakly-stored callback no longer resolves to a live object

update()stops running on x-limit changes- the plot stays stuck in whichever mode it started in (like envelope as was the case)

So the core bug is not "callbacks can't attach twice." It's:

The object that owns the callback can be garbage-collected immediately, so adaptivity silently disappears.

That explains why "keeping the return value" fixes the bug: by doing that, we end up providing the missing strong reference!

The first fix idea: retain adaptors per Axes

Once we know the problem is "the adaptor dies," the first fix was simply to keep adaptors alive somewhere internal, so users don't have to remember to store the return value. Since adaptors are conceptually "attached to an Axes," store them per Axes. So we might do something like:

# A module-level dictionary that lives for the lifetime of the program

_adaptor_registry = {}

def waveshow(y, sr, ax, ...):

adaptor = AdaptiveWaveplot(...)

# ... set up the adaptor ...

# Store it in the registry so it stays alive

_adaptor_registry[ax] = adaptor

return adaptorA registry here is just a module-level dictionary, that is, a global container that outlives any single function call. By storing the adaptor in this dictionary, we create a strong reference that persists even after waveshow() returns. The adaptor won't be garbage-collected because the registry still points to it.

Now the adaptor has a strong reference from the registry, and it won't be collected. But then comes the second requirement: we must not create a memory leak. If a user closes a figure or throws away an Axes, we don't want our registry to keep it alive forever. For this, WeakKeyDictionary could be the perfect tool.

WeakKeyDictionary explained

To use weakref.WeakKeyDictionary was Brian McFee's idea. I didn't know about them before. It's like a dict where the keys are weak references.

That means: If the key object (here: an Axes) becomes unreachable everywhere else, Python can garbage-collect it, and the entry disappears automatically.

So this sounds perfect:

weak_key_registry[ax] = adaptorSo this keeps the adaptor alive, but doesn't keep the Axes alive. The problem here is that values can keep keys alive. A WeakKeyDictionary only drops entries when the key becomes unreachable.

But if the value stored in the dict holds a strong reference back to the key, then the key never becomes unreachable. In that case, the "weakness" of the key doesn't matter, because the object graph still has a strong path keeping it alive. And in our situation, that can happen very easily.

Remember the earlier detail: artists strongly reference their Axes. Originally, the adaptor held strong references to artists:

- adaptor → steps artist

- adaptor → envelope artist

And artists reference their Axes:

- artist → Axes

So if we retain the adaptor globally, we can accidentally create:

registry value → adaptor → artist → Axes (registry key)

Even though the key is "weak", the value keeps it alive and so the entry never disappears. Therefore the "minimal fix" does fix the bug… but it risks pinning Axes/Figures in memory.

The real fix: retain adaptors and break strong adaptor → artist → Axes links

The final solution has two deliberate parts which work together.

Part A: Keep adaptors alive per Axes

Add a module-level registry (a WeakKeyDictionary keyed by Axes) to retain adaptors, as discussed, to guarantee users can ignore the return value and adaptivity still works.

Part B: Make the adaptor hold weakrefs to Axes and artists

To prevent the registry value from pinning the registry key, I had to change the adaptor to store weak references to: the Axes and the artists it manages (steps/sample and envelope). So instead of the adaptor owning those objects strongly, it just "points at them if they still exist."

Then expose @property accessors so existing internal/external code can still do adaptor.ax, adaptor.steps, adaptor.envelope without rewriting everything.

And because weakrefs can return None once something is collected, update logic in update()/disconnect() to handle "the thing I used to manage is gone" gracefully. This is the heart of the safety fix: it breaks the strong cycle that would otherwise prevent cleanup.

Why the tests matter (they prove both behavior and safety)

To be honest, I only found ou about the memory leak after I wrote the tests. And I didn't even thought it would be so important, since I had managed to "fix" the bug with the naive fix. Brian was the one who suggeted it, and when I wrote it and it failed, I noticed "yeah, this guy knows a whole lot more about this than I do."

Behavior tests: adaptivity survives garbage collection

First I wrote tests to specifically test the bug scenario:

The test calls waveshow() without storing the return value, forces gc.collect(), zooms via set_xlim, draws the figure, and then asserts that the sample artist is visible and the envelope artist is hidden (or performs equivalent checks via ax.lines / ax.collections).

We do it for single and multiple waveshows. That directly includes the user promise: "It should adapt even if I ignore the return value."

Safety test: registry doesn't pin Axes/Figure in memory

This is the subtle one. We avoid pyplot globals (since pyplot can hold references behind the scenes), create figures/axes directly, detach axes from the figure, delete references, force GC, and verify that the Axes actually gets collected and the registry no longer contains the Axes key.

A mental picture to remember the whole thing

Before

The adaptor has no strong owner after waveshow() returns. Since Matplotlib stores callbacks weakly, the adaptor gets garbage-collected immediately if the caller ignores the return value. The callback stops firing, and the display stays stuck.

Naive retention

Storing adaptors in a registry fixes the bug, but creates a trap: registry → adaptor → artists → Axes forms a strong reference cycle. The WeakKeyDictionary can't drop entries because the value (adaptor) keeps the key (Axes) alive through the artists.

Final fix

Break the cycle by making the adaptor hold only weak references to artists and Axes. The registry keeps the adaptor alive, but there's no strong path back to the Axes. When the user closes a figure, the Axes can be garbage-collected and the WeakKeyDictionary entry disappears.

Takeaways that be useful in the future

- Registering a callback does not necessarily mean "this thing will stay alive." It depends on whether the framework stores callbacks strongly or weakly.

- WeakKeyDictionary is not a magic "no leaks" solution. It only works if keys can truly become unreachable.

- In Matplotlib, artists often strongly reference their Axes. That makes "value accidentally pins key" a common trap.

- The robust pattern here is to retain what we need for behavior, but weaken internal references to avoid memory pinning.